By Katie Finch, Senior Nature Educator

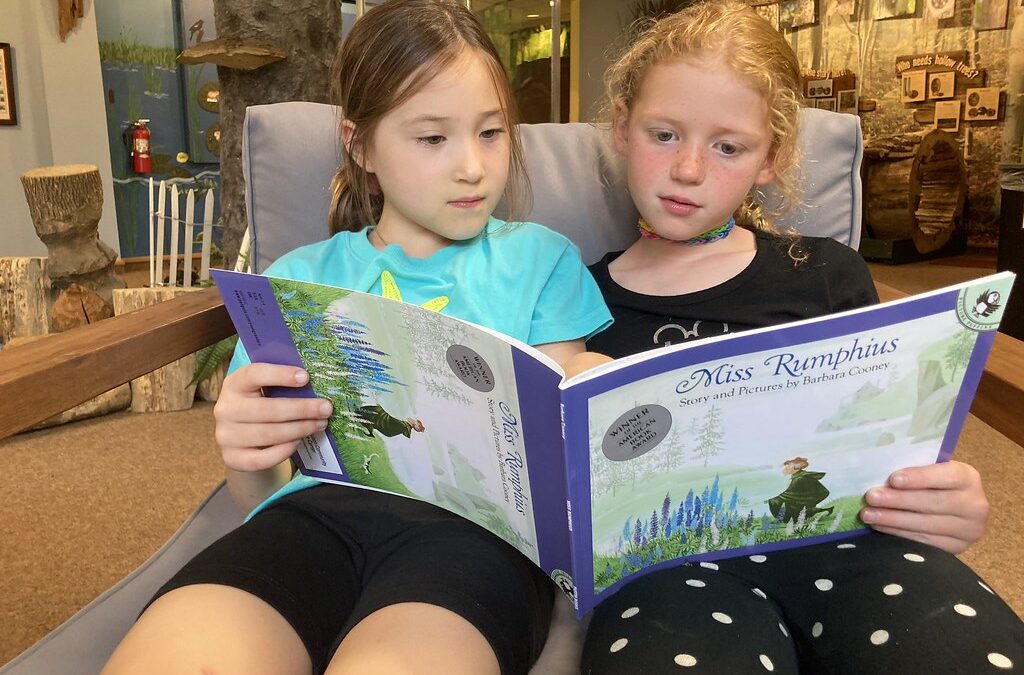

I love children’s picture books. Their simple, yet often powerful, stories capture my imagination and each illustrated page is a work of art. As a kid, one of my favorites was Miss Rumphius, written and illustrated by Barbara Cooney.

It is a story of Alice Rumphius, who lived by the sea and grew up listening to stories of her grandfather. Her grandfather immigrated to America and worked as an artist. Alice, too, wanted to travel to faraway places and live by the sea when she got older. Her grandfather told her there was one more thing she had to do in her life. She must do something to make the world more beautiful.

Alice grows up and travels to tropical islands, rugged mountains, deserts, and jungles. And when she gets old, and goes by Miss Rumphius rather than Alice, she finds a little cottage by the sea. She observes the ocean, plants a small patch of lupine flowers, and begins to contemplate how she can make the world more beautiful. After watching the lupines spread naturally from her garden to new places, she knows what she wants to do. She orders bushels of lupine seeds, fills her pockets, and spreads them as she walks. The following springs, lupines bloom everywhere she walked.

This book is packed with themes that resonate with my past and present self. I share Miss Rumphius’s sense of adventure, independence, and her loving relationship with a grandparent. The story also highlights what life can look like when we age, models a way to connect to nature, and the importance of beauty.

I like this story because it emphasizes the act of creating or nurturing beauty can be a measure of a successful life. But recently, I started looking at Miss Rumphius’s beautiful deed differently. With a better understanding of how plants and animals interact in their environments, I started to wonder what specific seeds Miss Rumphius spread? In the book, the lupine plants spread quickly and profusely. The illustrations show brightly colored stalks of pink, purple, and blue flowers thickly growing along the shore, behind the buildings, and along roadsides. They look and sound beautiful. They also sound non-native and invasive.

Non-native invasive species are organisms that are introduced to a new ecosystem and cause some kind of harm. Plants and animals that have not evolved over time in an ecosystem with the other living things may be out of place. There may not fit into the existing food chain and can crowd out native species.

Many invasive plants hitch rides in ships’ ballasts, packing material, or with other plants and are spread unintentionally. Other invasive plants are introduced intentionally, without understanding their impact on the environment. For example, Water Chestnut was introduced to North America as an ornamental plant. At Audubon, we now hire seasonal staff to keep this invasive plant from covering our ponds.

The story of Miss Rumphius and her lupines was inspired by the author’s own adventures as well as the real-life story of the “Lupine Lady”, Hilda Hamlin, who spread lupine seeds along the Maine coast.

Today in Maine and many other eastern and midwestern states, Lupinus polyphyllus, commonly called Bigleaf, Marsh, or Western Lupine spreads across summer fields. It evolved to be a part of ecosystems in western North America. Scientists estimate that this lupine species was introduced to the eastern region as an ornamental plant and quickly spread beyond gardens in the 1950s. It quickly crowded out the native Lupinus perennis, commonly called Wild Lupine or Sundial Lupine.

Both lupine species are beautiful. And both provide benefits to the rest of the ecosystem. Like other legumes, they can take nitrogen from the air and make it available to plants through the soil. Insects gather nectar and pollen from the flowers. It is only the native Lupinus perennis, that is a food source for the endangered Karner Blue butterfly.

Monarch butterflies and milkweed are a well-known, exclusive relationship. But there are others. Just as Monarch caterpillars only eat milkweed, Karner Blue butterflies only eat this particular species of lupine. Without Lupinus perennis, there will be no Karner Blue butterflies.

I am drawing my own conclusions about lupine species in this story based on my observations and experiences. This children’s book doesn’t address this. But I do ask myself, does this new perspective make me like the story of Miss Rumphius any less? No. It is still a beautiful book with an important message. It reminds me of a quote attributed to Maya Angelou. “I did then what I knew how to do. Now that I know better, I do better.”

We can only work with the information and experiences we have. This is true in our relationships with others. It is true for the choices we make that affect our environment. We are constantly learning more. That’s the wonderful thing about the world. There are always more questions to ask and curiosities to wonder about. Like Miss Rumphius, having adventures, connecting to nature, and learning from others can help us make the world better and more beautiful.

Audubon Community Nature Center builds and nurtures connections between people and nature. ACNC is located just east of Route 62 between Warren and Jamestown. The trails are open from dawn to dusk and birds of prey can be viewed anytime the trails are open. The Nature Center is open from 10 a.m. until 4:30 p.m. daily except Sunday when it opens at 1 p.m. More information can be found online at auduboncnc.org or by calling (716) 569-2345.

Katie Finch is Senior Nature Educator at ACNC.

Recent Comments