By Chelsea Jandreau, Senior Nature Educator

Creativity and science are sometimes viewed with an antagonistic relationship. In school, maybe you were good at art, but didn’t get great grades in biology, or maybe you were great at math, but couldn’t draw more than a stick figure. However, separating creative and scientific minds does us a disservice, as they are often heavily intertwined both historically and in today’s world.

When many people think of creativity, they think of drawing or sculpting, of someone creating a work of art, or an artist whose painting is hanging in a museum. Creativity is more than that though. It is using your imagination and problem solving. It is producing something to express an idea or feeling. It is also finding new solutions to an existing question or problem. These are concepts that are vital to scientific discovery and learning.

For me, creativity is not the consistent presence I wish it was, and instead comes in waves. Sometimes I wonder if this is because most of my crafting muses and imagination-fueled works are based in nature. My embroidery motifs are usually botanical. My knitting and crochet are usually in colors inspired by the seasons. My favorite nerdy tabletop game scenarios to craft are the ones where I am carefully choosing creatures, even if they are imaginary, to match the habitats and biomes my players wind up in.

For me, this means that although winter holds a number of fascinating and beautiful things, after a few months of bare trees and snowfall, I’m ready to move on to color and more obvious signs of life in the natural world. When spring starts slowly arriving, in the forms of chipmunks above ground, flocks of Red-winged Blackbirds, or the sight of actual grass revealed by the melting snow, I start to feel that spark of creativity again.

Spring is also the time when I tend to come back to one of my least impressive talents – drawing. Objectively, I am not a talented artist, but luckily for me, that’s not the point. The point is observing and documenting what I find inspiring or interesting. I have notebooks full of drawings, annotations, and observations that are dated primarily March, April, and May, and little else from any other month.

While this could be considered a creative endeavor, recording observations through drawing has also historically been a scientific pursuit. Much of our present documentation of nature comes in the form of photography, but this was once a less readily available medium and so we have a wealth of illustrated natural specimens from the 1800s, and dating back hundreds of years before that as well.

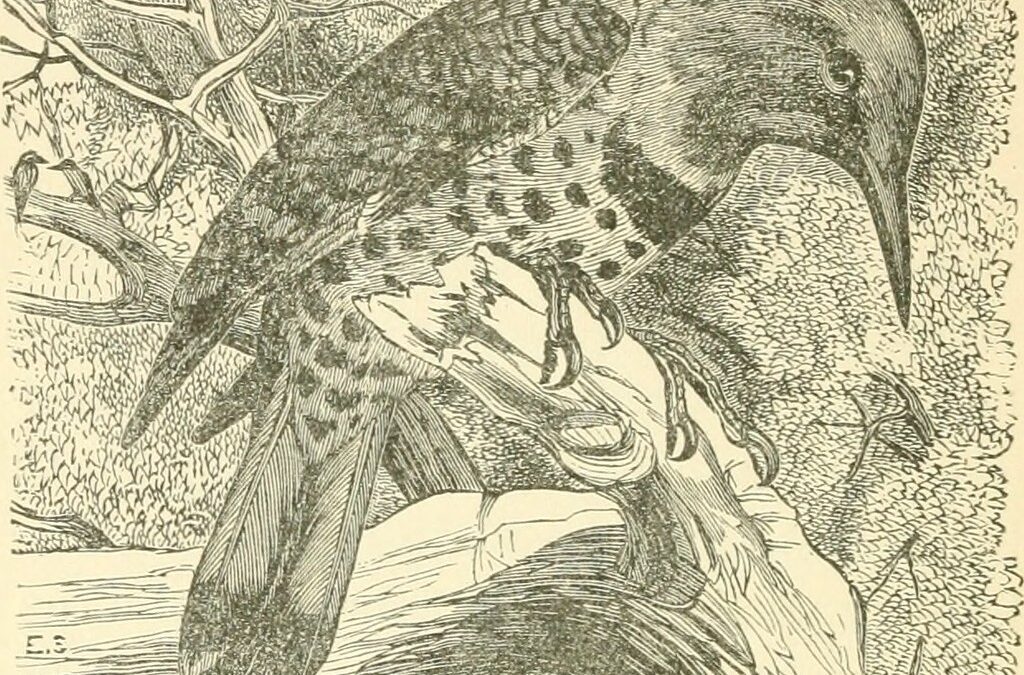

Some of these illustrations are published and well known. You may have seen them in field guides, like John James Audubon’s “Birds of America” or “The Sibley Guide to Birds” by David Sibley. Birds are a popular subject of study among naturalists, but there are plenty of others throughout history who spent their time drawing, painting, and annotating other organisms.

Insects, plants, and fungi were popular subjects of naturalist illustrations, possibly because they could all be contained well enough to keep them still. With many species, specimens were killed and preserved for study, but the illustrations allowed accurate depictions of these animals to be shared with more people in the scientific community and beyond. These illustrations, often with field markings, were used both by the broader community of naturalists and by professional organizations. For example, Sherman Foote Denton is known for his watercolor fish illustrations commissioned between 1895 and 1910 by the US Fish Commission, which would later become the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the NYS Forest, Fish, and Game Commission, now the Department of Environmental Conservation.

There were naturalists collecting and documenting through illustration around the world, and this number included many women. Scientific illustration became an avenue for women to enter the field of wildlife research and documentation, when other doors may have been shut for them at that time.

Florence Merriam Bailey was one of the most prominent female scientific illustrators within the United States. She was an ornithologist who made most of her observations outside, watching the behaviors of living birds, rather than studying preserved specimens. She published several books including, “Birds Through an Opera Glass”, a field guide for North American birds, and “Birds of Village and Field”, a beginner birder field guide.

Violet Dandridge was one of the first women employed by the Smithsonian as an illustrator. She worked alongside Mary Jane Rathbun, the first full-time curator at the museum. Her drawings captured accurate details in invertebrates and plants. Anna Comstock was another entomologist and scientific illustrator, along with the first female assistant professor at Cornell University, and an advocate for nature education. She and her husband illustrated textbooks on invertebrates.

Maria Sibylla Merian was an entomologist from Germany and throughout the late 1600s and early 1700s created detailed works of plants, insects, and other arthropods. She was particularly influential to those who wanted to learn more about where insects came from as she sketched and painted detailed accounts of many insect life cycles.

Sometimes the people who embarked on a journey to document nature through illustration had training, while others were exposed to it through family members. Some had formal art training, and others just had years of practice. You don’t have to produce works of art worthy of publishing to create your own scientific illustrations either.

When you take this style of scientific illustration, with its focus on observation and accurate records, and make it a personal pursuit, it is often known as nature journaling. If you are interested in diving right in, John Muir Laws has a book dedicated to improving both observation skills and techniques in nature journaling. You can also start smaller. All you really need is paper and something to draw with. Take a seat, find something interesting, and just start drawing and writing down what you see. You might be surprised at the details you find when you start looking at the details of the things you look at every day.

Audubon Community Nature Center builds and nurtures connections between people and nature. ACNC is located just east of Route 62 between Warren and Jamestown. The trails are open from dawn to dusk and birds of prey can be viewed anytime the trails are open. The Nature Center is open from 10:00 a.m. until 4:30 p.m. daily except Sunday when it opens at 1:00 p.m. More information can be found online at auduboncnc.org or by calling (716) 569-2345.

Featured image: Northern Flicker. Illustrated by Florence Merriam Bailey.

Recent Comments